centaurs, triple threats, and jacks of all trades

the case for generalists

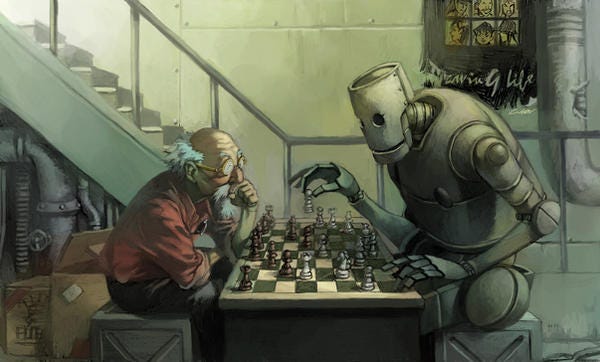

Chess is a game of war. It’s a clash of intellects, a contest of tactics and strategy. Tactics — the traps and maneuvers — are the short-term battles one uses to gain a material or positional edge over an opponent. Tactics are often trained out of pattern recognition, from studying analogous scenarios time and time again and calculating possible permutations a few steps ahead. Strategy, on the other hand, is the long-term vision of how to win the war.

1997 - Gary Kasparov, the reigning world chess champion, was defeated by Deep Blue, IBM’s chess supercomputer.

1998 - Kasparov organized the first Advanced Chess tournament, where each human player was paired with a chess engine. In a 6-game series, he tied 3-3 against a player that he had defeated 4-0 in a traditional match a few months prior.

2005 - The first Freestyle Chess tournament takes place, with teams of humans, computers, and humans + computers (centaurs). A centaur team of two amateur chess players and three supercomputers obliterated the competition, including Hydra (the world’s strongest supercomputer at the time) and grandmasters assisted by computers.

The victory of the centaurs showed the world that it was neither humans nor computers that reigned supreme. It was humans who synergized with computers, leveraging the strengths of both parties. Top teams leveraged computers for the short-term computational power to identify winning tactics, while humans were responsible for thinking beyond the current stage of the game toward a winning outcome.

This is one of the opening stories from David Epstein’s Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, a book given to me by a close mentor of mine. This piece is a pre-reading (27 pages in, I’ve put the book down and opened Substack) braindump on my existing thoughts on generalists.

tactics in the product trifecta

Much like how computer engines shook the world of chess, AI tools are changing the game for the Product Trifecta (Engineers, Designers, and PMs). Github Copilot effectively autocompletes code, while DeepCode’s Snyk detects vulnerabilities and automatically them. Uizard uses designer text inputs to auto-generate whole user interfaces, while Visily uses AI to uplevel designs from low-fidelity to high-fidelity. And, of course, most of the chatbots built on the foundational models can write PRDs, build GTM strategies, and perform basic data analytics techniques.

This graph is only going up and (obviously) to the right. Models will continue to get more advanced, more versatile, more capable. As this happens, their propensity to perform tactics will rise in ways we will be forced to adapt to. The strongest operators, then, will be the centaurs capable of harmonizing their inherent human strengths with machine intelligence, unlocking outcomes beyond anything either man or machine could accomplish alone.

So how do we get a head start?

“I think fundamentally there are two strategies to build on AI right now. There’s one strategy which is assume the model is not going to get better and build all of these little things on top of it. Then there’s another strategy, which is to build assuming that OpenAI is going to stay on the same trajectory and the models are going to to keep getting better at the same pace. It would seem to me that 95% of the world should be betting on the latter category.”

— Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI, former President of Y Combinator)

problem spaces

Conventionally, consumer AI products have been most prevalent in the form of chatbots. They require some text input from the user to generate an output. They require a problem to generate a solution. The more I learn about Product, the more I come to recognize the importance of defining problem spaces.

Not only is this exercise crucial in enabling PMs to define success and align product strategy with market opportunities, but it is also essential for the other branches of the trifecta. Designers need clearly defined problem spaces to flex their creative muscles to create optimal user experiences, while Engineers need them to guide critical architectural decisions and enable effective feature prioritization.

I believe that problem space definition is a key arena in which generalists maintain dominance over specialists. Having domain expertise in a breadth of functions throughout a business or even throughout one workflow in a business will inform higher-level perspectives that a siloed operator could never hope to possess. This birds-eye view of the big picture enables solutioning that integrates seamlessly with the rest of the pieces of the puzzle. Better yet, generalists who wield both this broad understanding and the skills to execute can go ahead and solve the whole puzzle themselves.

“The people who have been the most valuable are the ones who can wear multiple hats.

→ The designer who can code

→ The PM who can also write great copy

→ The customer support person who knows how to sell

These are the people who can take an idea and run with it, without getting bogged down in the handoffs and bottlenecks that come with specialization.”— Grant Lee (Co-Founder & CEO of Gamma)

a jack of all trades

“A jack of all trades is a master of none,

but oftentimes better than a master of one.”

— Robert Greene (Old English Dramatist), on William Shakespeare

I’m sure that as much as I rave about generalism now and optimize for learning and breadth of knowledge, I’ll inevitably become increasingly specialized in both role and industry as I progress in my career. So, to my future self, here’s where I am in all of this at present.

I recently joined a seed-stage consumer AI Stealth startup for “Product.” I put the word in quotes because — as everyone said I’d be — I’m doing it all. I’m on the ground doing user interviews at college campuses, effectively asking folks in our target market for feedback on our product while selling it to them. I’m ideating PGC for the content team and have just recruited another student to share this responsibility with me. I have, of course, built PRDs and Figma mockups, though I’m delighted to find that there’s virtually zero latency between discovery and deployment.

The speed and range are certainly stimulating factors. It’s what I dreamt of, after my brief and slightly existential foray into big tech. But what I hadn’t anticipated quite as much was the ambiguity. The lack of someone to hold your hand, a manager to hide behind. Here, I truly manage the products, and I can see how the lack of guardrails may induce anxiety in some. In others, however, this ambiguity manifests as the airspace necessary to spread wings and take flight. To learn about anything and everything, and output consistently throughout. And most importantly, the pursuit of product-market fit has been one of the most creativity-intensive exercises to date in my professional journey. We’re practically looking at a blank canvas, but again — there’s a fine line between despairing and feeling energized by this limitless expanse of possibilities.

executive summary, for now

In a world where we increasingly outsource our tactics with technology, our ideas and vision soar take utmost importance. The attributes that make people uniquely human – curiosity, creativity, empathy, imagination, intuition – coalesce with breadth of experience to create the most operating potential. As machines evolve, so can we by doing, creating, and building.

Now, I’m no executive, and I’m not even close to being a SME in anything other than credit card churning and Pokémon Go. But I am willing to bet that even at such an unprecedented point in history, history will repeat itself. And when the dust settles, centaurs will yet again come out on top.